Spring 2023

Group members: Brianna Butler

ABSTRACT

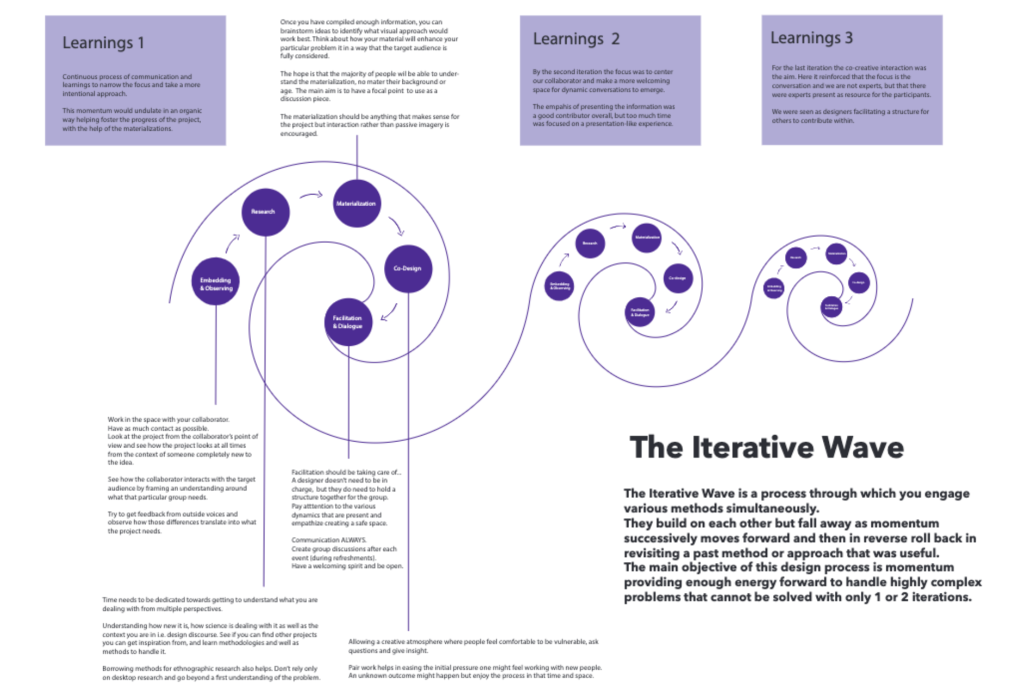

The current approach to facilitation has numerous benefits but lacks sufficient challenge in raising awareness about wicked problems. This project was conducted in collaboration with the organizational context of a plastic-free store in the Gothenburg area. Focusing on the wicked problem of microplastics and its impact on us and the environment, we proposed a practice that can assist designers in addressing complex issues. By combining a systematic view with methods such as embedding, research, materialization, co-design, and facilitation, we arrived at a hypothesis for a new practice called The Iterative Wave.

This method, presented as a template, offers insights and instructions for other designers to utilize in similar contexts. The project also includes discussions on the project’s sustainability, ethics, and ideas for future continuation. The project encompasses two dimensions: the socio-political environmental dimension and the embedded design dimension, as further explored below.

RESEARCH QUESTION

From a design standpoint, we seek to demonstrate how designers can address complex is-

sues connected to the current state of the world, often referred to as “wicked problems.”

Our project responds to the research question of how aesthetic objects can be utilized

in interactive settings to evoke empathy for complexity, ultimately instigating change

through imagination. Recognizing that small actions can make a difference, given the

significant damage caused by tiny particles, we became ambitious in our perspective on

addressing the issue.

PROCESS

Event 1 with EkoSpeceriet:

After organizing the first event in collaboration with Mimbly (see project Plastisphere), we recognized the importance of emphasizing the impact of microplastics on the human body. The audience showed a desire for more explanations and insights into how microplastics circulate and affect us. We successfully engaged participants in discussions, prompting them to question their behaviours and consider changes to reduce their own consumption. The event also sparked speculations about future possibilities, such as microplastic-free labels on food. However, we identified the need for improved logistics and space arrangement, as well as more interactive materializations and co-creation opportunities for participants.

Building a network within the city and involving a researcher in the field were also crucial for fostering a passionate community. Moving forward, we took on these learnings and applied them on when we ideated for the second event.

Event 2 at Mimbly:

In our second event, our focus shifted towards increasing awareness among non-designers and fostering co-creation with participants and external partners in an organizational context. We aimed to create actionable solutions and bring about a shift from an individualistic to a community mindset. Reflecting on this event, we recognized the importance of requiring participants to invest time or engage in discussions to access relevant material. We also acknowledged the challenge of maintaining participants’ attention and focus for extended periods due to a general competition for attention. However, we found that investing in process activities could influence participants’ actions and their perception of personal impact. On the organizational side, we reaffirmed the need for win-win relationships and ensuring that collaborations evolve and thrive despite differing expectations.

By navigating through these stages and events, we have continuously learned and refined our approach to address the complex issue of microplastics and foster meaningful change.

METHODS

Embedding: We immersed ourselves in the context by spending time with our collaborator, having tea, and engaging in conversations about the store’s goals and values. This helped us observe their sustainability practices and understand their approach to spreading the message to customers. It also allowed us to establish a deeper relationship with the collaborator and gain insights into their customer demographic and behavior.

Interviews: We conducted interviews with various individuals, including experts in the field and random people on the street. These interviews provided us with valuable resources, ideas, and feedback, and helped us expand our network and explore new possibilities.

Workshops: We organized workshops to engage participants and learn from their experiences and perspectives. Through group discussions, we fostered a sense of community, gained a deeper understanding of the topic, and received constructive feedback for improvement.

Desktop Research: Given the complexity of the microplastics issue, we conducted desktop research to understand the topic, gather relevant information, and stay updated on emerging scientific findings. This research informed the content and knowledge we shared with participants.

Ethnographic Research: We arranged a guided tour at a local wastewater treatment plant to gain a better understanding of how microplastics are handled locally and identify areas for improvement. This provided a valuable perspective from experts in the field.

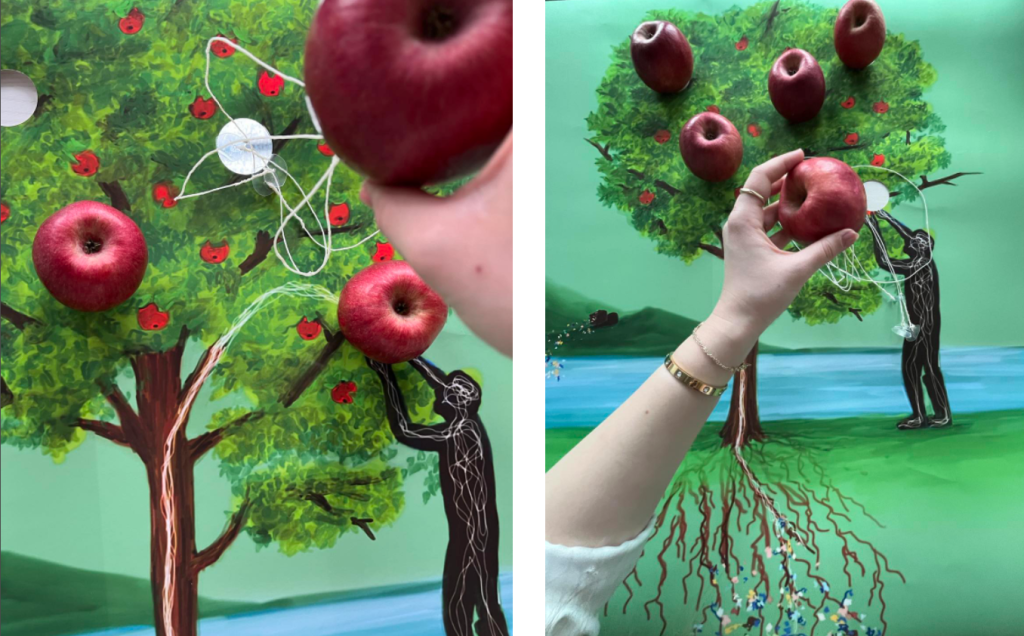

Crafting/Materialization: Visualizing the issue of microplastics was crucial in making it accessible to a wide range of people. We used crafting and materialization techniques to create aesthetic objects that could effectively communicate the invisible problem and provoke engagement and interaction.

METHODOLOGY

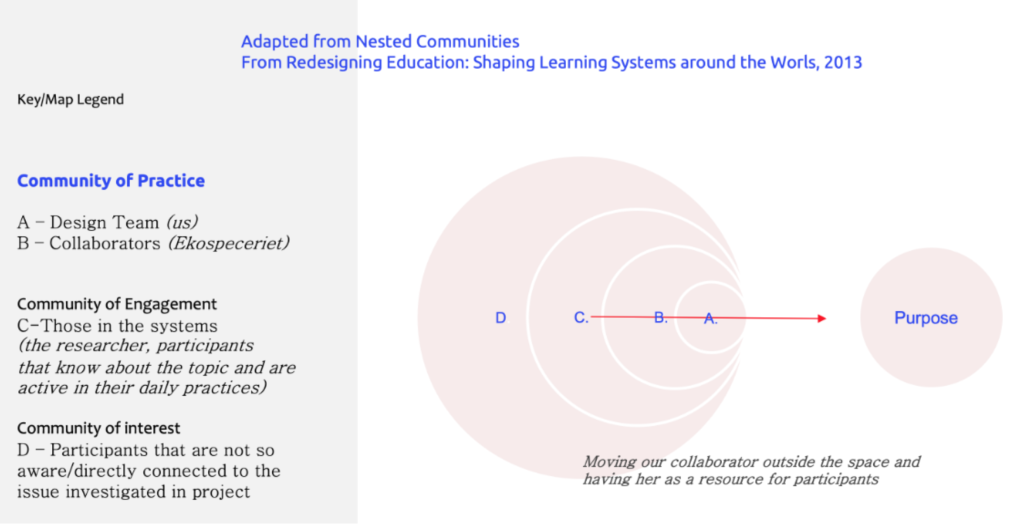

To create a community of practice and drive change in the field of microplastics, we adopted the Nested Communities model and drew inspiration from Redesigning Education to understand how to transform a system. We recognized the importance of shared concerns, problem-solving, and knowledge creation among community members to advance the professional practice domain.

MATERIALIZATIONS

Throughout the process, each method was chosen intentionally and served a specific purpose. The combination of these methods allowed us to build a community of practice, generate knowledge, and drive meaningful change in addressing the issue of microplastics. The approach taken in this project aimed to create material objects that would serve as focal points in various spaces and facilitate dialogue. The inspiration behind this approach stemmed from the need for tangible items that could evoke emotions and establish connections, ultimately bringing visibility to otherwise invisible entities.

Drawing from Wulia’s work (2023) on the significance of aesthetic objects as links between imagination, emotions, and institutions, it was evident that such objects possess the ability to create social networks and act as catalysts for social change. Examples of aesthetic objects highlighted by Wulia include archives, exhibition catalogs, and socially engaged art. In the context of this project, the aesthetic objects created served as powerful tools for engaging individuals and fostering empathy. Participants became more aware of the personal impact of microplastics and gained an understanding of their circulation through water, air, and soil.

The realization of how materializations could be featured and utilized in a space was influenced by a notable installation called “A Subtlety” by Kara Walker. This artwork shed light on the historical exploitation of people of color in the sugar trade, specifically those involved in sugar cane harvesting and the impact of slavery. The deliberate placement of the installation in the old Domino Sugar factory in NYC, facing Manhattan, added to its significance. The site itself, with its decaying state and panoramic views of the city, contributed to the overall ambiance. The core of the massive focal point—a naked woman of color – was made of polystyrene, covered with 80,000 pounds of refined white sugar. This depiction served as a thought-provoking commentary on race, particularly from the perspective of an American artist. Complementing this focal point were life-sized sugar cast children holding basins of molasses, emitting the scent of molasses as the sugar sculptures began to melt from the heat.

The juxtaposition between the macro element and life-sized objects in our own project echoed the impact it had on viewers. By directly drawing attention to the scale of the issue and providing real-life counterparts alongside our materializations in the second workshop, participants were able to make connections and contemplate their own interactions with food. This comparison framed conversations around the potential for replacing plastic items with plastic-free alternatives. The goal of utilizing materials to generate discussion and create memorable talking points proved successful, as evidenced by the engaged conversations observed among the participants.

In summary, the materializations created in this project served as focal points to facilitate dialogue and raise awareness. Inspired by the power of aesthetic objects, as highlighted by Wulia, and influenced by Kara Walker’s “A Subtlety” installation, these material objects sparked conversations and encouraged participants to reflect on their relationship with microplastics and alternative solutions. The utilization of materials proved effective in generating impactful discussions and leaving a lasting impression on participants.

FACILITATION APPROACH

In terms of facilitation, we employed a co-design approach to integrate diverse perspectives and ideas from participants, aiming to foster a collective understanding of the issues and solutions related to microplastics in the present moment. Drawing on the insights of Mosely et al. (2021), we recognized the role of a designer facilitator in guiding participants, users, and stakeholders through the design process to encourage new ways of thinking, doing, and problem-solving. To immerse participants in spaces associated with plastic consumption awareness, we intentionally chose workshop venues that were connected to or aligned with the mission of changing our relationship with plastic. This setting reinforced the narrative that people are concerned about the plastic problem, and our project aimed to engage more individuals in the movement to reduce plastic usage and exposure. By creating a dialogue in a

safe and comfortable space, we fostered openness and care within our community. We established a safe space by using psychologically-safe statements that encouraged opinions, questions, and feedback. Statements such as “Feedback is okay,” “Opinions are okay,” “There are no stupid questions,” and “It’s okay to be unsure/not know” allowed participants to express themselves without fear.

Empowering individuals and fostering a sense of togetherness were crucial for creating an emerging community in the city, as observed in our previous events where a relaxed environment led to heightened creativity. Recognizing the need to build rapport among participants, we incorporated icebreaker activities after reflecting on our initial workshop. By providing a relaxed starting point, we aimed to encourage quick bonding among strangers, facilitating co-creation and open conversations. To enhance idea exchange and support conversation, we opted for one-on-one interactions rather than group settings. Working in pairs allowed for a team dynamic to develop, reducing pressure compared to presenting ideas to a larger group. Additionally, we provided prompts during exercises to assist participants in their creative journey and maintain momentum, especially for those who struggled to generate ideas independently.

A key activity during the workshop involved displaying real fruits alongside fake ones, serving as a visual reminder of the invisible microplastics plaguing our food. This juxtaposition provided a playful illustration of the scale at which microplastics operate, highlighting their invisibility to the naked eye. We also designed a 3D apple-picking activity where participants interacted with an infographic, triggering a moment of realization. The combination of a real apple placed on top of an infographic depicting the circulation of microplastics evoked strong emotions and deepened understanding, as participants engaged in the experience without prior expectations. The aesthetic objects served as focal points,

effectively expressing how invisible particles directly impact our food.

Overall, our facilitation approach embraced co-design, safe spaces, icebreaker activities, one-on-one interactions, vivid visual representations, and a focus on shared reflection and commitment. These strategies helped foster collaboration, empathy, and meaningful dialogue among participants, ultimately contributing to the formation of an engaged emerging community.

RESULTS – THE ITERATIVE WAVE

The iterative wave approach allows for the simultaneous engagement of various methods to address complex issues like microplastic pollution. It acknowledges that no single approach or solution can encompass the entirety of such a multifaceted problem. Instead, it emphasizes the importance of continuous momentum and iterative cycles to gradually build understanding and create meaningful change.

In the context of addressing microplastic pollution, the use of aesthetic objects in interactive settings proved to be an effective strategy. By providing tangible objects and opportunities for personal interaction, participants were able to develop a deeper relationship with the issue and empathize with its complexity. This approach surpassed the limitations of 2D imagery or generic graphics by creating a space for questioning, vulnerability, and shared experiences among participants. Group discussions and dialogues further facilitated connections between the experience and participants’ daily lives, enabling faster recognition of interconnections and personal relevance.

Through these methods, we immersed ourselves in a continuous process of awareness and action, driven by our intentions and the urgency of the subject matter. Stepping back to examine different perspectives and understanding how information is processed in terms of actions and emotions provided valuable insights for our next steps. Meaningful interactions and discussions, particularly those focused on environmental issues and interconnected systems, highlighted the importance of making aspects of the problem accessible and relatable. The sculptures we created were tailored to convey a more personal experience and underscore the connection between human health and our relationship with

food within the broader environmental context.

During the materialization process, the size and presence of our objects played a role in eliciting reactions and engaging with the opinions of others. Feedback from passersby and collaborators proved productive and pushed us further in refining our approach. Their perspectives and insights served as valuable input to inform our ongoing process of iteration and improvement.

In summary, the iterative wave approach, coupled with the use of aesthetic objects and interactive settings, allowed us to immerse ourselves in the complexity of microplastic pollution. It fostered empathy, dialogue, and a deeper understanding among participants, while feedback from external sources provided valuable guidance and contributed to the evolution of our work.